Let’s face it: we’re spoiled when it comes to comic book cinema. We don’t just have a glut of films that can seemingly turn the most fringe favorite into a household name, and intricately crafted universes. Even before those, we marveled at the glitz and polish of current comic book adaptations. But the genre’s jump to live-action has humble beginnings. The likes of Shazam, Superman and Spider-Man garnered adaptations decades before, making their mark on TV and film serials. These early attempts remain endearing despite their low budgets and DIY depictions of the characters and powers. That being said, they aren’t that easy to watch knowing what’s now at our fingertips. However, there is one of these progenitors that stands out as perhaps the oddest of them all: 1974’s Wonder Woman TV movie.

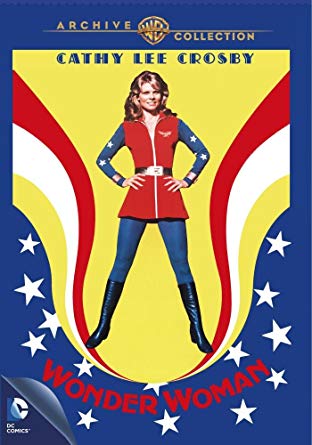

This failed ABC pilot turned syndication staple pre-dates the well known Lynda Carter TV series of the same name by one year. Starring former tennis pro and infamous Wrestlemania 2 commentator Cathy Lee Crosby, the film marked the live-action debut of the most beloved super heroine in DC’s pantheon. But not in the form that most fans might recognize.

RELATED: New Teaser Posters For Wonder Woman 1984 And Birds of Prey Released

The Crosby version of Diana was based on the “New Wonder Woman” run that lasted from 1968 through 1972. The change saw Diana renounce her Amazonian powers and receive a mod makeover. She discarded her iconic costume for the latest in late-’60s garb. Left powerless, she trained extensively in martial arts with blind master I Ching (ages well…) to remain formidable. The result was a modernized, military-aligned blip on the comics radar that underwhelmed once the initial shine faded away.

This is the Wonder Woman with which audiences were faced. A secret weapon of the American military posing as a CIA receptionist. Running into battle in a proto-pantsuit was totally mod. With a grappling hook belt buckle in place of her trademark lasso.

So why go this route when trying to prove the commercial viability of arguably the most successful female-led comic series in a new medium? The “mod” experiment ended with much publicity two years before the film’s debut. That should have been plenty of time for producers to realize what the Wonder Woman fan base wanted. A depowered hero arguably makes for an easier, cheaper, production, but the success of the retooled Wonder Woman series that came after calls that into question.

The best answer lies in the reasoning behind the creation of the “New Wonder Woman” in the first place. A more humanized hero could allow for more interesting stories. The transition was also financially motivated, as the book was in danger of cancellation at the time. But the move also opened up new lanes of creativity to explore. From government espionage to battles with mythological creatures, the new Diana had a much larger range of evils to fight. And her connection to her own humanity blossomed. Diana of Themyscira wasn’t reduced by becoming a powerless figure who split her time between the U.S. government and a boutique shop. She was made more whole.

RELATED: Patty Jenkins Teases Plans For Wonder Woman 3

No facet of this incarnation supports that claim more than Wonder Woman’s increased connection to the burgeoning women’s liberation movement. She was already a prominent feminist figure in her original form, but her more relatable presentation heightened her visibility as a gender-equality advocate. Wonder Woman was now less different at her core than the young woman reading her book. Her strength seemed that much more attainable for the marginalized that identified with her.

Unfortunately, this connection to the women’s liberation movement would spell the end for the “New Wonder Woman.”

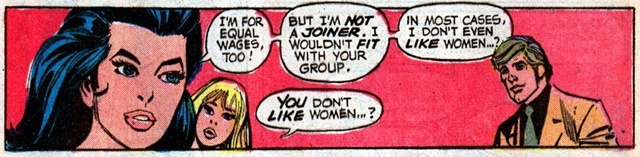

Her over-reliance on male companionship and increased propensity for violence during this era persisted as points of contention for a movement stressing independence and non-violence. But those critiques paled in comparison to Wonder Woman # 203, a “Special Women’s Lib Issue.” 203 showcased Diana Prince’s alliance with women’s liberation advocates by ruminating on interstate commerce law. She outright states that she doesn’t “even LIKE women” in most cases. She needs to be convinced to join the movement against the gender wage gap. Never a stronger ally has existed.

The issue ends with a group of black women confronting Diana for causing them to lose their jobs by protesting an offending department store. It’s a cliffhanger that is never answered. This is how the experiment ends. The revolutionary hero has to be convinced to join the movement she is meant to embody. She becomes a tool to take a final dig at feminism. Before cloaking her in her leotard again.

To call this a failure at discourse is an understatement.

RELATED: Wonder Woman 1984 Gets Pushed Back To Summer 2020

Oddly enough, the 1974 film fails for many of the same reasons. This reinvention, supposedly infused with more feminist theory, falls flat in execution. The film showcases examples of an increased awareness well enough for the era. She spurns the constant bombardment of the male libido. The only major fight scene takes place between Diana and rogue Amazon Ahnjayla. But the fact that Diana smiles and casually dismisses every cultural transgression with a laugh feels eerily similar to Diana’s disconnect in her final depowered chapter. It’s no wonder that ABC deemed the Crosby entry a failure after the fact, giving way to the character’s more traditional presentation. Presenting the message without the tenacity only serves to muddy it within a poorly crafted film.

Sometimes accuracy in adaptation isn’t always the best thing.